Andy Crouch wrote A World Without Jobs in response to Steve Jobs, CEO of Apple, announcing that he is taking medical leave. Crouch, he contrasts the hope offered by Steve Jobs' "secular gospel" with Barack Obama's expression of hope in his recent speech at Tucson after the shooting there. Jobs' gospel, according to Crouch, is technological progress and courage in the face of death found in a meaningful life here and now. (Jobs' thoughts on the matter are expressed well in his commencement address at Stanford; I recommend watching this.) Jobs, on death:

No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don’t want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it. And that is as it should be, because death is very likely the single best invention of life. It’s life’s change agent; it clears out the old to make way for the new. Right now, the new is you. But someday, not too long from now, you will gradually become the old and be cleared away. Sorry to be so dramatic, but it’s quite true. Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma, which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice, heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become.

Crouch says, in response:

Upon close inspection, this gospel offers no hope that you cannot generate yourself, and only the comfort of having been true to yourself. In the face of tragedy and evil it is strangely inert. Such a speech would have been hard to take at the funeral of Christina Taylor Greene, nine years old, killed along with five others on a bright Saturday morning in Tucson, Arizona. It is no wonder that Barack Obama, who had to address these deeper forms of grief this past week, turned to a vision which only makes sense if there is more to the world than we can see. Anything less is cold comfort indeed.

Which is the better source of hope: this world, small, and often backwards as it is, but certain, or transcendent meaning and eternal life, known by invisible evidence? What can comfort? In Obama's speech at Tucson, he presents both of these ideas of hope, and this is most apparent in his remembrance of Christina Taylor Green, the nine-year-old who was killed in the shooting. First, the secular hope:

I believe we can be better. Those who died here, those who saved lives here—they help me believe. We may not be able to stop all evil in the world, but I know that how we treat one another is entirely up to us. I believe that for all our imperfections, we are full of decency and goodness, and that the forces that divide us are not as strong as those that unite us.

That's what I believe, in part because that's what a child like Christina Taylor Green believed. Imagine: here was a young girl who was just becoming aware of our democracy; just beginning to understand the obligations of citizenship; just starting to glimpse the fact that someday she too might play a part in shaping her nation's future. She had been elected to her student council; she saw public service as something exciting, something hopeful. She was off to meet her congresswoman, someone she was sure was good and important and might be a role model. She saw all this through the eyes of a child, undimmed by the cynicism or vitriol that we adults all too often just take for granted.

I want us to live up to her expectations. I want our democracy to be as good as she imagined it. All of us—we should do everything we can to make sure this country lives up to our children's expectations.

Contrast this with his more symbolic and religious appeal to hope:

Christina was given to us on September 11th, 2001, one of 50 babies born that day to be pictured in a book called "Faces of Hope." On either side of her photo in that book were simple wishes for a child's life. "I hope you help those in need," read one. "I hope you know all of the words to the National Anthem and sing it with your hand over your heart. I hope you jump in rain puddles."

If there are rain puddles in heaven, Christina is jumping in them today. And here on Earth, we place our hands over our hearts, and commit ourselves as Americans to forging a country that is forever worthy of her gentle, happy spirit.

May God bless and keep those we've lost in restful and eternal peace. May He love and watch over the survivors. And may He bless the United States of America.

(Emphasis mine.)

Crouch closes his article:

Steve Jobs’s gospel is, in the end, a set of beautifully polished empty promises. But I look on my secular neighbors, millions of them, like sheep without a shepherd, who no longer believe in anything they cannot see, and I cannot help feeling compassion for them, and something like fear. When, not if, Steve Jobs departs the stage, will there be anyone left who can convince them to hope?

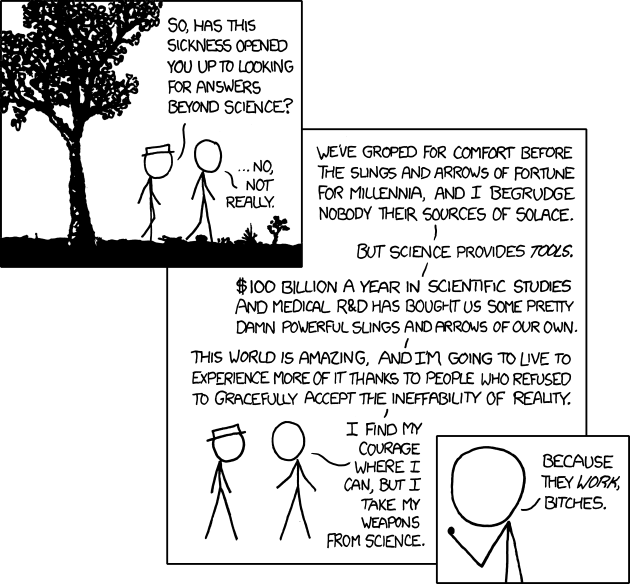

The question of what is the better hope to offer someone who is suffering, "Certain goodness in the material world, though modest and mixed, or possible perfection from above?", this question is an empirical one, if subjective. I offer for consideration my story as a case. As I was deconverting, finding the claims of Christianity to be dubious, I was upset at the loss of the hope from heaven, hope for a better life in eternity, and hope for justice in this world; the loss of these beliefs was the most painful element of my doubt. I don't miss these at all now, though, and I shudder when people like Andy Crouch say that I should feel like my worldview offers only "cold comfort"; I don't need his compassion and I don't need him to fear for me on account of my naturalist worldview, and I find these offers condescending.

Since I accepted my nonbelief, about a year and a half ago, I've been consistently happy in a way that I haven't been since I was a kid. I have a rabbit and I enjoy chili and reading books and doing my job and going to the beach with friends. Jobs' commencement speech reminds me of the motto, memento mori, remember to die. I understand that my life is finite and I occupy myself with making the most of it now: enjoying it for myself, loving the people close to me, and trying to do work that is useful for strangers. This attitude clearly doesn't work for everybody, but looking for hope from somewhere outside of the universe hasn't worked for me.

I'm thinking now of conversations with religious friends, concerned that I, an atheist, am deprived of hope. I hope that they can accept that I have a happy, meaningful life, and that it is possible to have hope without God. I hope that my friends who doubt are not pained by the threat of a loss of hope, that they can peacefully consider their beliefs. I hope that when humans suffer, we would be filled with courage, regardless of our source of solace.